Korean contemporary art is currently enjoying unprecedented global visibility. From the reopening of the Korean Art Gallery at the Peabody Essex Museum to the acclaimed traveling exhibition “Hallyu! The Korean Wave”—currently on view at Museum Rietberg in Zurich after its debut at London’s V&A and stops in Boston and San Francisco—Korean art is commanding institutional attention across continents. That energy has now made its way to New York, where three exhibitions offer a timely counterpoint, turning our gaze to the roots of this momentum: the rich and experimental legacies of 20th-century Korean modernism, shaped by political upheaval and transnational displacement.

Since the mid-1950s, Korean artists have built a long arc of global engagement—now they are reshaping the map of contemporary art. As Kim Daljin—founder of the Kimdaljin Art Archives and Museums and a leading chronicler of Korea’s contemporary art scene—has noted, Korean art began appearing abroad as early as the 1950s, though it only gained consistent visibility in international programming in the decades that followed. This gradual rise reached a new level of prominence around 2022, when Frieze launched its first fair in Seoul, capitalizing on the surging market and scholarly interest in the postwar movements, such as Dansaekhwa (“monochrome painting”). But only recently has Korean art history started making its way into the biggest museums in the US. When the Guggenheim Museum staged “Only the Young,” a survey of Korea’s postwar avant-garde, in 2023, it was the first show of its kind at this institution.

That shift can be seen outside New York as well, of course. A recent show at the Denver Art Museum showcased moon jars, including treasures on loan from the National Museum of Korea, and the newly expanded Korean gallery at the Peabody Essex Museum reintroduces key works from the museum’s holdings. And there is more Korean art history on the horizon, with Dia:Beacon set to exhibit recently acquired works by Lee Ufan next year.

How will that history be told going forward? Three New York exhibitions, reviewed below, offer some clues.

-

Chang Ucchin at the Korean Cultural Center New York

Image Credit: ©2025 Chang Ucchin Foundation, All Rights Reserved “Chang Ucchin: The Eternal Home” is a quiet milestone. It’s the first New York solo exhibition dedicated to the revered artist (1917–90), a key figure in Korea’s first generation of modern painters. Long celebrated alongside Kim Whanki, Park Sookeun, Lee Jungseob, and Yoo Youngkuk, Chang’s work is modest in scale yet expansive in affect. “I’m a simple person,” he liked to say—a mantra embodied in his lifelong pursuit of purity through form. His distilled motifs—suns, trees, houses, birds—become sparse, resonant symbols of memory, longing, and metaphysical stillness. In The Persimmon Tree (1987), a stark white tree anchors the canvas, its branches alive with movement beneath a pale mountain ridge, flanked by a floating red sun and blue crescent moon—an elemental universe rendered with childlike clarity and spiritual weight.

Co-organized with the Chang Ucchin Museum of Art Yangju, this show features over 40 works, including rarely seen paintings, drawings, and prints. At its heart is A Family Portrait (1972), a tiny painting of a door within a door, behind which a family quietly peers out. Thoughtfully installed in a recessed black alcove, the work acquires architectural resonance: its spatial nesting echoes the work’s emotional interiority. The painting alludes to the artist’s separation from his family during the Korean War and memorializes an earlier family portrait he sold in 1955—his first artwork ever to find a buyer—to purchase a violin for his daughter. The painting acts as a compact but resonant form of remembrance.

In the center of the gallery, viewers are invited to flip through the pages of Golden Ark (1992), a limited-edition art book published by the Limited Editions Club of New York—the only one in its history to spotlight a Korean artist. Personally curated by Chang from over 730 oil paintings, the volume features 12 works meticulously reproduced to match their original scale and color, preserving the intimacy and precision of his vision. The show opens a window onto Chang’s inward gaze, where modernism becomes a vessel for stillness, solitude, and the enduring poetics of home.

At the Korean Cultural Center New York, 122 East 32nd Street, through July 19.

-

“The Making of Modern Korean Art: The Letters of Kim Tschang-Yeul, Kim Whanki, Lee Ufan, and Park Seo-Bo, 1961-1982” at Tina Kim Gallery

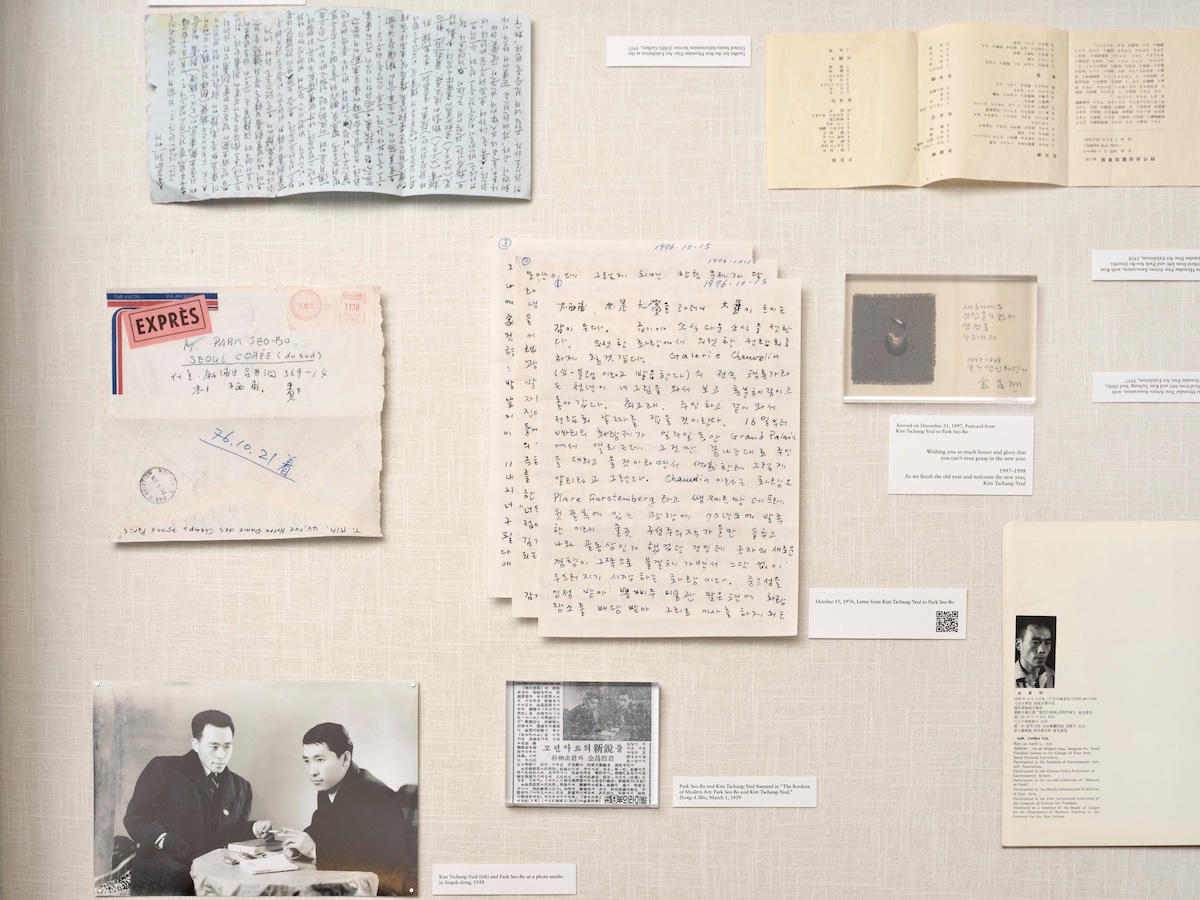

Image Credit: Hyunjung Rhee/Courtesy Tina Kim Gallery More than a historical survey, “The Making of Modern Korean Art” is a reminder that modernism was not merely an aesthetic—it was a shared way of living formed through correspondence and mutual exchange. Organized in tandem with the launch of a landmark English-language publication of the same title, this scholarly, archive-driven exhibition brings to light the unpublished letters of four key figures in postwar Korean art: Kim Whanki, Kim Tschang-Yeul, Lee Ufan, and Park Seo-Bo. Spanning over two decades, the letters chart the intellectual, emotional, and geopolitical currents that shaped the emergence of Korean modernism.

Displayed alongside seminal early works—including Park’s Ecriture No. 65-75 (1975), Kim Tschang-Yeul’s Waterdrops (1975), Lee Ufan’s From Line (1977), and Kim Whanki’s transcendent dot painting from his New York period (1971)—the letters function not as context, but as parallel material: intimate, ideologically vibrant, and often profoundly vulnerable. They oscillate between practical logistics and philosophical musings, and reveal a shared urgency to define a modern Korean art distinct from Western paradigms and the cultural authority of established norms and traditions.

A standout example is a 1973 letter from Kim Whanki to Kim Tschang-Yeul that offers a poetic reflection on the “Waterdrop” series: “It looks like drops of perspiration, not water. You worked on it so hard. … [It would be] good as a great desert, a broad plain; the more fervent the inspiration, the more earnest it seems.” The letter reveals how artistic labor was both observed and deeply felt between peers—modernism here emerges as an intimate dialogue shaped by mutual care, critique, and emotional investment.

This communal spirit could also be felt during a panel this past May at Asia Society, where a group of people associated with the book—co-editors Yeon Shim Chung and Doryun Chong, contributor Kyung An, and Lee himself—reflected on the project’s long gestation. Lee spoke candidly about the need to resist absorption into Western-centric narratives. Their correspondence, as the exhibition reveals, was a lifeline—a form of mutual recognition and radical endurance.

At Tina Kim Gallery, 525 West 21st Street, through June 21.

-

“Heryun Kim: The Great Tomb of Hwangnam and Other Paintings” at Bienvenu Steinberg & C

Image Credit: Photo by Inna Svyatsky/@installshots.art Heryun Kim’s US debut centers on a monumental installation of 164 ink drawings inspired by the elaborate metal saddle excavated from the Silla dynasty’s Hwangnam Daechong tomb. Each drawing features thick, black, maze-like lines on colored grounds—suggestive of calligraphy or circuitry—that appear methodically patterned at first glance. But, as Kim notes, “There is no identical rule. The lines vary, little by little, every time.” What emerges is a rhythmic field of difference—a visual code embodying the time, labor, and ancestral rhythm.

Originally trained in German literature, Kim turned to painting after concluding that “images were more primal and powerful than language.” Her practice is deeply rooted in material encounter. She often reflects on the differing resistances of ink, oil, and paper—and how these affect her brushwork, timing, and gesture. Inspired by Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro, Kim regards Korean black ink (muk) not merely as color, but as force—viscous, alive, and sensorially charged. Some works were painted with her eyes closed, allowing sensation rather than sight to guide her.

Kim’s abstraction is anchored in Korean heritage: roof tiles from Goguryeo tombs, Neolithic pottery, dolmens, and oral rhythms all leave their trace. “I believe one must truly understand the roots of their own culture before they can understand others,” Kim has said. This ethic guides her decades-long engagement with Korean history through drawing, museum research, and site visits. Echoing comb patterns, architectural silhouettes, or ancient script, her brushstrokes are charged with both personal intensity and cultural weight. She creates a space for viewers to dwell with the ancestral, embodied, and the not-yet-deciphered.

At Bienvenu Steinberg & C, 35 Walker Street, through June 14.